This week saw the introduction of our final research project for the term, where we discussed the themes we would be interested in developing.

At the start of the week we were tasked to find an essay online related to our particular interests. I decided to read the article ‘Expanded Architecture’ by Sarah Breen Lovett. It explores how moving image installation can be used to explore our relationship with architecture, and how this relationship can be altered or changed. This is a topic that I have had a longstanding interest in and have explored within my own artistic practise, particularly during my time at the Arts University Bournemouth.

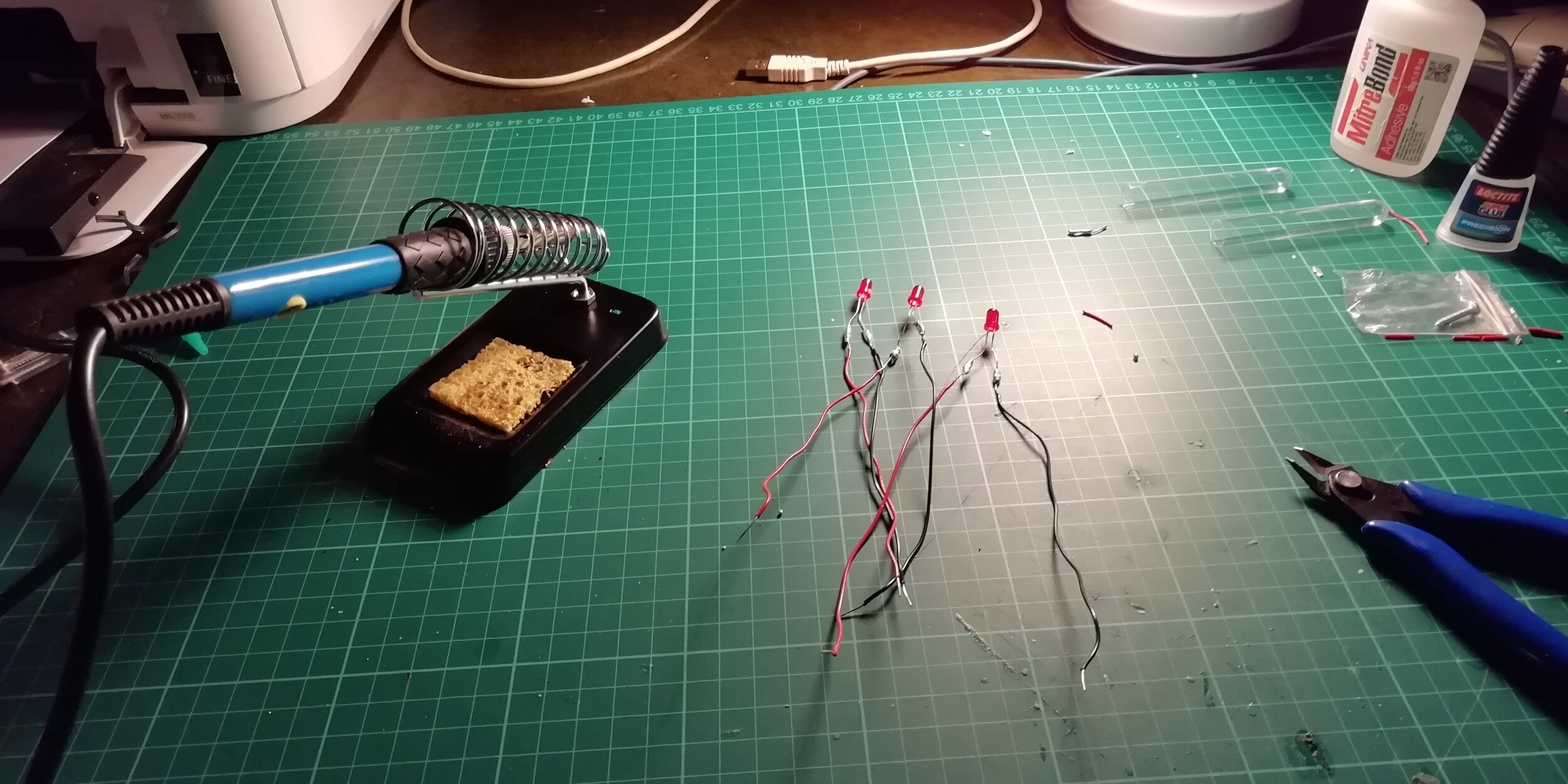

During my time at AUB I became very interested in experimenting with techniques such as circuit bending and video feedback, creating psychedelic imagery that I would across different surfaces and buildings. I was particularly intrigued as to how I could use these projections to facilitate reactions from passersby. The buildings at my university were used daily and designed for a specific purpose; by casting psychedelic imagery across them I was able to create environments that affected how people would interact with the space.

This is a theme that is covered by Lovett in the essay. She mentions how the pairing of moving image and architecture operates in contradiction:

Architecture is normally experienced in a state of distraction, while art work, whereas film is experienced in a state of awe. By reframing the architecture back on itself, this inherent contradiction leads to an interesting wavering of consciousness between the moving image installation, and the architecture. By using one to explore our relationship to the other, a third entity is formed. One is not totally ignorant of the architecture, nor in awe of the moving image, but sits in tension between these elements. Lovett, 2011

Lovett goes on to explain how these contradictions creates a certain tension between self and space, as the architecture that we have grown accustomed to suddenly becomes unfamiliar. It reminds me of a piece by Rachel Ara, displayed at the Barbican in late 2018:

The piece uses a mixture of film and CGI to create a mirror image of the Barbicans iconic architecture, making references to film history, utopian architecture and contemporary politics. It acts as a glitch, a window through which the observer might catch a glimpse of the future. (Ara, 1018).

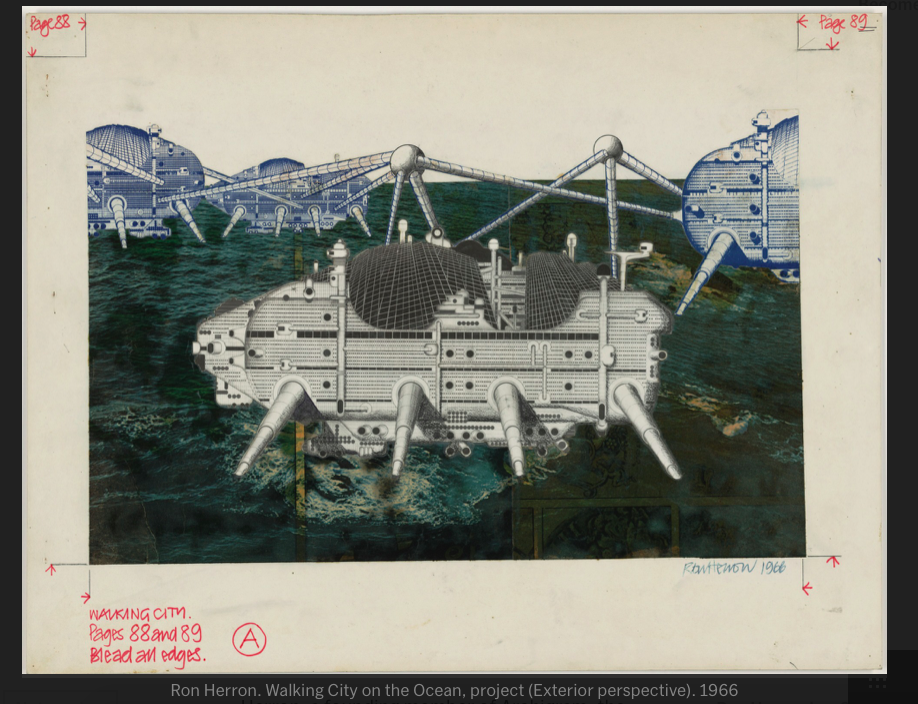

Towards the end of our session we split into various groups and discussed potential research topics. I mentioned my interests in architecture and the notion of utopia, particularly how visions of the future from the 20th century are viewed differently today. I am interested in how a vision of utopia can change and become dystopian over time; an example of this can be seen in the work of Le Corbusier and his plans for a city of the future:

This design was originally intended as a utopia; however in retrospect I feel the identical, repetitive buildings look distinctly dystopian. I feel if I am to work on this theme I need to consider how I can implement computation; in the past I have been interested in how generative art can be used within the construction of buildings - this is a topic related closely to my current research, with potential to be developed into an interesting project if explored further.

Bibliography

https://www.2ra.co/amerianbeauty.html

https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/11076/11077